When I’m in the crowd I don’t see anything

My mind goes a blank, in the humid sunshine

When I’m in the crowd I don’t see anything

Paul Weller/The Jam

I love the glory of afternoon walks in the Essex countryside. But in winter, darkness falls too quickly on the unlit lanes and muddy footpaths stretching towards the Blackwater estuary.

Instead, I head for the Chelmsford lights, where any number of outlets sell coffee. Those with outside tables and chairs win, because of my aversion to crowds. I sit and sip quietly, snug in coat, gloves and hat. Observe the bustle. Quietly, unobtrusively at the centre. Enjoying the snatches of conversation drifting my way.

My own company feels good. I’ve come to realise that I’m an introvert. That looking inwards makes me like myself. That I’ve been introspective for decades.

The lack of daylight exacerbates that feeling from November to February. It has taken time to be comfortable telling people that I don’t want to join or be part of any group except close family. To just say: ‘I’m not interested’. As the years pass, I’m better at owning it.

It’s a puzzle to some – and I get it. Groups are the essence of everyday life.

A month or so back I had to attend a large family gathering. About 25 good people, many of whom I love dearly. Much mingling and laughter.

(Relaxed parts of myself are left at the door. Even when nothing is wrong, it drains me to be around lots of people. Even when everyone is known, and kind.)

There were a couple of good, open conversations over the four hours. A fun bit of football outside with the kids. And the inevitable ton of small talk.

(My nature is to tune into feelings around me. Can’t help it. An empath. Metabolising all the visual and speech clues. All the voices at different pitches, overlapping conversations, shouts, laughter. Boundaries that shift. It doesn’t help to have my ears screeching from tinnitus. Scanning the room, I’m soon tense, overstimulated. Who looks out of it and might need company? Finding even a few sentences takes effort, feels like performance.)

As usual, I kept the stress internal. Banged a huge, heavy lid on top of it. Near the end, I grabbed my grand-daughter’s pushchair to pack in the car. Outside, I suddenly realised I didn’t need to return. Why not stay here and wait for wife Maureen, daughter Lauren and her daughter Fox? (Nobody will mind). I sighed with happy relief.

The simple act of saying goodbye to a crowd is a gauntlet. I know – it’s bog-standard social protocol. But I feel such discomfort. Maybe it’s autism? Mixed with feelings that much of the ritual is meaningless?

Or maybe just growing into my true self with age? 69 this coming March.

In recent years, the tinnitus has played its part in decisions to avoid gatherings where big noise is probable. New hearing aids have helped a little in masking the ever-present discordance in my ears. I’ve also come to realise how alcohol has been a priceless crutch down the years, getting me through social situations by desensitising.

The notion of introversion – and of struggling to function in daily life – is hinted at in my domain title.

This was the nickname given to the wing of a mental institution in ‘Where my Heart Used to Beat’, a book published by Sebastian Faulks in 2016. The book’s narrator and his colleagues decide to ditch traditional categorisations and contexts (schizophrenia, paranoia, Freudian analysis etc). Instead, they just relate to the ‘patients’ as humans. The ‘doctors’ tell their own truths and acknowledge their own vulnerabilities as they sit in the wing alongside the ‘mad’ men and women. They accept the voices besieging the inmates as authentic. And some successes are recorded in restoring wider functions of sanity.

When I read the book in 2019, that theme of absolute, reciprocated empathy more than struck a chord. It lit me up. (Conversations with no holds barred, listening and hearing, no ego, no sarcasm or dismissal, all subjects eligible….yes please, please yes).

Faulks’ fictional unit was a country cousin to how I operate in company, tuning easily and without judgement into the wavelengths of friends and strangers. But (for me) paying a price. The usual lop-sidedness of listening hard without sufficient reciprocation.

So, I wondered if I could set up an online form of Biscuit Factory. To tell unashamedly and truthfully – and hopefully with a dose of wit – of past and present joys and traumas. Ecstasies and sloughs. Maybe like wearing my filthiest underpants outside my cleanest trousers. The biggest aim was to boost my introvert’s sense of limited self-expression. And to trigger some feedback and two-way conversation.

In my honest experience, groups, especially all-male gatherings, generally bring a plague of non-listening, hierarchy and performance.

15 years ago, I had to walk away, forever, from two guys I met for a drink every week. They talked and talked, Steve in particular. Not so much banter and piss-taking (which would have been equally annoying, after a few novelty minutes). In this case, it was using 25 sentences where 10 would do (edit yourself, FFS). Whenever I had something to say, it would often be interrupted or overruled in favour of a laugh or louder point of view. Schoolyard stuff. A smouldering store of resentment began to build. At some stage, a group nickname appeared, the Three Musketeers.

Ludicrous.

My smile was often rictus. The alcohol helped dull the pain. My own fault for ignoring stirrings of unease and letting regular drinking and cycling partner Tony persuade me that Steve should join us every Wednesday night. The last straw came when they tried persuading me to join their French skiing weekend, after I’d said clearly that I didn’t have the time, money, experience or desire.

(They have even found me a crash course for beginners. They haven’t fucking listened. Or taken me seriously. Or think they know better. From any angle, it’s parachute time.)

“Three’s a crowd”, I explained, by text. Not sure they understood but being free of them was like being able to breathe cleanly again. The break led me into three new (mainly solo) activities that are core now: walking, meditating and blogging. That change, and my agency in it, started a process where I became less mutable and pliant.

I’ve always been fine with huge crowds. Happy as Larry to slot into the groupthink of football gatherings or music gigs where you lose yourself in the focus and excitement. Maureen and I are off to see Nick Cave again, at Brighton in July. Can’t wait.

Smaller events like weddings and parties would be more problematic. I can see that I’ve used alcohol liberally to fit into those one-off gatherings.

I just can’t hack smaller groups. These are a form of captivity if any regularity gets established. Even in threesomes, hierarchies form. I go quiet until sure that people want my contributions.

(Ask me how I am and mean it. Let me take my time. I am an introvert, and write better than I speak. There will be gaps, where I’m thinking, but don’t interrupt. Keep listening, like I do to you).

About seven years ago I hooked up with half a dozen or so men and women who purported to want big social and political change. Radical ideas floated around at the first meeting, at a house in Great Dunmow, Essex. The topics fascinated me. Money, politics, medicine, self-sufficiency. But by the third (last) time I turned up, mutual respect was thinning and egos coming to the fore. Roles were being invisibly allocated.

(The reverie is always to quietly grab my coat, exit calmly, then sprint away, chuckling out loud at my escape).

A couple of years earlier, I tried a ‘men’s evening’ in our village, Great Waltham. There was a talk on global warming. Most of the guys knew each other. They chatted and laughed through the talk. Regularly interrupted the speaker. One of them told me that a group from the village holidayed together each year. 30 to 40 of them. I wasn’t envious.

Am I just shit at being in groups? Not necessarily. Three exceptions stand out, led by closest family. My three kids have real skills. If you speak at the same time as them they step back happily and let you go first. Chip off the old block. My wife is the same. Egos held in check, they tend to throw out love, humour, irony and gentle self-deprecation. No ganging up, no shouting, no disparagement. If there’s a debate, the other side’s point gets acknowledged. I’m proud to be in their gang.

Another was a Buddhist group I joined in 2011-12. It offered a fellowship, as all members were trying to lift the levels of their practice, and would help each other to that end. I always looked forward to Friday nights. The gentle humour, the discussion, smell of the incense and the feel of a deepening mystery amid the collaboration. Egoless togetherness.

I also love participating in a couple of online groups, but that brings no physical obligations. You can turn off or ditch the phone whenever you want.

Whereas protocols like Zoom and Microsoft Teams make me feel mentally ill. Everybody compressed into the same artificial screen space. When talking to somebody (singular or plural) by phone, I want to scratch my arse, pick my nose, fidget around and maybe sigh quietly in soft exasperation rather than be viewable real-time in a linear screen.

Clearly they are seen to be great for long-distance family link-ups. All I can see are templates that limit and reduce most users to a shadow of their fullest selves. I don’t care if you disagree.

Where do these struggles of mine originate? Dad certainly brought me up to obey. To defer or be hit. To stay in the cage or be punished. Mum came at me from a persuasion angle. “Be nice, please people. Do it to make me happy Kevin.” Was that inadvertent preparation for group conformity?

They did their best, bless them. I was a happy kid. But senior school sculpted my complying proclivities into a more strangled shape. Aged 13. I was contentedly embedded, still freely expressive, in a social group in my second school year. Relaxed, doing well academically, good at sports. Issues of trust and shame then shattered and stripped my confidence. Trauma for my still unformed personality. I was so upset that “friends” could humiliate me.

Shit happens so survival instincts kicked in. Not standing out. Gritting your teeth. Holding yourself in the shape that others expect. And listening hard for oncoming humiliations, to get ahead and dodge them.

I should have worn glasses from about the age of 14. Reading the blackboard in winter was a nightmare of squinting, finding excuses to sit near the front or copying from a classmate. To prevent ridicule for being ‘four-eyed’. Standing at bus stops on dark afternoons, I couldn’t read what number bus was coming.

As I got older, telling jokes became a favourite mode of affiliation. (Get them laughing, and you’ll be better liked.) As did the simple trick of asking questions. Giving others licence to talk was mightily effective in staying low and keeping aligned.

Thankfully, solo actions let in breezes of liberation. From 14 to 18, I would often travel alone on the train from Pitsea to East London to watch West Ham, my football team. A first, often dangerous glimpse of men behaving impolitely. Swearing, drunkenness and hooliganism. Then solo visits to music gigs at the Southend Kursaal. The loud sounds of Status Quo, Deep Purple and the Faces, containing hints of unknown freedoms and pleasures. Girls dancing wildly. A few independent thoughts started to blossom. These were teased out further by the colourful journalism in the New Musical Express. Music opened doors to other worlds. Art, literature, alternative culture.

Knowing I would be free of school at 18, I went through the motions. Did my homework. Stayed below the parapet. Grew my hair, tucked into the pack. Began the business of romance, hoping to find throbbing hearts beneath brassieres. Somehow captained the cricket team, despite zero interest in leadership. Age 17, I decided to quit my French A-level, as I was falling behind in the subject. I consulted nobody, parents included. My decision, my consequences. (Yes!!) At age 18, when exams finished, I left immediately. Money could be earned. No waiting for ‘Leaver’s Day’ nonsense.

The urge to do my own thing, away from known practices, was heating up.

Drifting into university life, I stumbled on a pot of gold in Birmingham. New, exhilarating, trusted alliances. Mates from Manchester, Newcastle, Liverpool. Breakout. The wildest friendship group I’ve known. (Do you like a laugh, can you court trouble and drink like a fish?) Two particular years of unrestrained joy, in the second half of the 1970s. Gallons of beer, fine romances, tall tales galore. Lines crossed. A criminal conviction. Hangovers to die from. Falling asleep drunk in snow. No student balls or other tame artifice.

And finding the courage to dance! So much more important than academia. Autumn 1977, at the university’s Northern Soul club. I said goodbye to the misery rituals of teenage discos. Here, people did their own thing, alone or in a group. Boys out on the floor with the girls, but the lads seemed to be thinking about their steps rather than pulling. Buoyed by ales, wearing my favourite baggies, I jumped in. The first few steps involved years of self-consciousness submitting to the untameable urge to move freely. Then into the flow, lifted by a surge of almost unbearable happiness.

Birmingham was a temporary fellowship nirvana. Containing the usual story whereby I simply refused to attend components of the courses that bored me or where I fell behind. Falling into line just felt…wrong. In the odd moment when I looked ahead the prospect of wearing a suit five days a week seemed like a form of insanity. Still does.

And so followed a string of madly individual decisions down the years. Learning to trust my gut. Very good and terribly bad choices. A headstrong cocktail referred to elsewhere in the Biscuit Factory. Best result of all – I met and hung onto a woman able to love me and tolerate my idiosyncrasies. But in 47 years of work life since 1979, almost 40 of those have involved operating alone. Sovereign. Away from scrutiny or control.

I couldn’t be a teacher because I can’t and won’t perform. So quit a training course after a couple of months. After spells as an ice cream salesman and betting shop manager, I became a milkman at age 29. Drawn by the prospect of fresh air, an early finish and no direct boss. I was on good terms with nearly all of the 30 or so fellow milkies. Get them alone and the conversation was usually positive, often helpful. In groups, the air turned blue, with almost everyone performing. At pains to underline that they were mavericks, cheating here, stealing there, cutting corners, doing the minimum.

I remember my 30th birthday. It’s funny now, but I despaired at being so old. At the end of the round, I climbed the fence behind the depot and went home a back way rather than face the half dozen or so guys standing by the coffee machine. I didn’t have the mood or energy to put on the group costume.

To be clear though. This is ultimately a positive story. Avoiding peer groups has big advantages.

For the last 30 years I’ve been a freelance journalist, maybe enjoying the final years of the profession before AI wipes it out. A suitable occupation, where I can be myself. Hard working, independent. Listening to music in my pyjamas and slippers as I type. Learning to write more clearly each year. Withdrawing more each year from what were once regular meetings and conferences in London. It has been exhausting at times. I’ve often been financially challenged. Sometimes turning day into night to hit deadlines but always trying to steer my own path. Unencumbered by woeful corporate cultures. No favours or sponsors. Sources checked.

Bottom line: staying solo is so goddamn freeing. It removes one of the shackles that weigh down all groups. You know it, deep down.

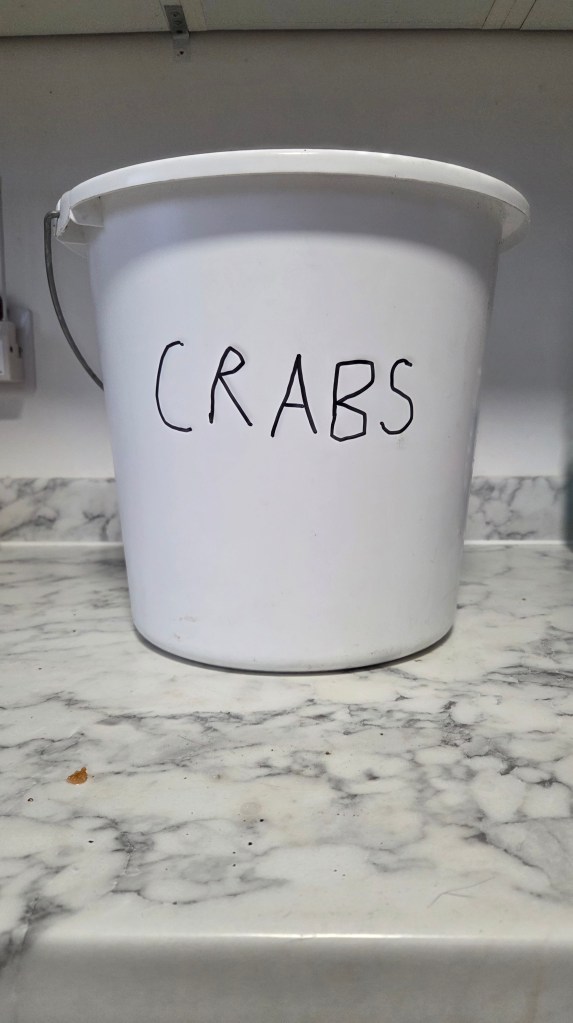

The opposite of a Biscuit Factory. The crab bucket.

That brilliant catch phrase for all of the tacit and overt limitations that define groups. For the taboos that hem in and pull down the members who want to climb higher, or right out of the bucket.

All those minutiae. Who decides the group agenda? Are there factions? Are certain types of humour (or cursing) disallowed or frowned upon? (I’m already out). Is there a group scapegoat? Do we have to wear a uniform of some kind? (Bye). Can we honestly talk politics, sex, gender or who we fancy? Can we show vulnerability? And who has the biggest or best (fill this in yourself – car, income, partner, house, kids, holiday, bodily part?)

I’m joyfully married to my missus of 40 years. Our morning chats are pure gold – like a holy sacrament, with few limitations that I’m aware of.

I’m lucky enough to count 12 or so very good friends, all of whom I would trust with my life. Get any of these on their own and the conversation flows like a swollen river. We swap exploits, loves, fears and worries. Laughing, relaxed enough to disagree. Two’s company. Two’s a real connection.

I’m ridiculously easy to get on with. Any subject under the sun is fair game. As long as there is no loud noise, I’ll listen hard and bounce your conversation back at you all day long. Never dismissing your ideas, or ridiculing, but teasing out your thoughts and telling my fund of stories when the gaps appear. Proper two-way stuff.

I counted five walking companions during 2025. Good times. Sunshine, beer, talk and laughter, out in nature. I’m planning to climb Ben Nevis this summer with one of those guys.

Most groups of any permanence rein back this type of closeness. They strip mine the honest intimacy I crave. Disagree all you like. Married couples meeting up? That might be an exception. I like that now and again. But let it become too regular and you will probably rub up against limiting tendencies. Like those crustaceans in their buckets.

Pure solitude remains a major aspect of my self-preservation. Every afternoon I try and walk 6 or more miles, preferably out in the countryside. Alone but never lonely. Sometimes I think I’ll keel over at the sheer bliss of being in nature. In the past few years, I’ve covered a fair chunk of the Essex coast and river banks. And lots of inland routes. Learning to identify birds. Burning down the belly fat. Becoming reasonably competent at capturing landscape in photographs.

I often find myself able to think more lucidly as afternoons unwind. Does being alone make for more accurate observing and discerning?

Who can say. But I do feel oddly confident that my atomisation over the years – allied to being a journalist and understanding how language is used – has turned on one lightbulb. That the people who run planet Earth are not our friends. And that the media that we read and watch and hear never, never state this absolutely bloody obvious fact.

It has been clear, for me, since the 2008 financial crisis. I wrote extensively about the untold trillions of private bankers’ losses bailed out by the public. But no arrests. No stop to the obscene bonuses. Why? So who is really running this show? Those nagging questions had me digging far deeper into the ‘news’. Pulling it apart and finding countless contradictions and absurdities. Realising that much of it is fabrication and manipulation. Hitler laid it bare, pointing out that people are more likely to fall for a big lie than a small one. He would have applauded the bold duplicities built into the official 9/11 and Covid-19 stories.

Paul Weller’s words at the top reminded me of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. That book describes beautifully how people can be conditioned to accept their servitude in herds, without resistance.

Weller’s “humid sunshine” is still here, fiercer than ever, in 2026. Humans walking along, eyes down, glued to their phones, while global reality is swiftly reorganising itself in alarming new ways. Driven by the same old political and business groups that never go away. Guilefully maintaining control using a mix of subtle manipulation and unsubtle distractions. But now coming into plain sight as being involved or complicit in murdering and raping children. No matter what colour their flag, what shade their politics, they lie to us, cover up deceit, wage war and harm us on a scale almost impossible to quantify.

They are racing to kill freedoms we once took for granted. Has there ever been a more critical time to trust our own observations? For the sake of younger generations coming through.

If being an introvert has helped in any way in waking me up to that, then I’ll take it.

Biscuits! Mate. I read every word of that thinking “I know, I know, I know” then the similarities in our geography hit. I too spent formative years in Pitsea. There’s something about that part of the world and groups and “you’re not doing it right if we’re not in big numbers” I too, don’t buy into that at all.

You’re a wise man. And I thank you for your post. To coin a modern parlance “I felt seen”

Now I’m not going to propose a meet up or anything but. When I walk in the hills near my home solo but for my dogs. I’ll think of you from time to time. Doing similar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Without the hounds. Thanks for the feedback Steve. It’s been a long winter and I needed to get that out of my system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s still a long winter for me for a while yet. I leave home in darkness return in darkness and do not see daylight until Friday afternoon. Soon I will get sunsets on the drive home. Then Sunrises on the way in. It’s glorious

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a prospect and a half to anticipate. That good old sun, what a pal!

LikeLike

A damned good read on a bleak Monday morning.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked it Mark. It shed a skin that I’ve been wearing for the past few months.

LikeLike

I loved this Kev. I had a relative who would just ignore what you wanted, and just go on and on and on. Trying to browbeat you into submission. I wrote recently that I am becoming quite misanthropic in later life. People’s lack of emotional intelligence astounds me. But also, like you I feel at peace in nature. Rich and I really do believe now we live in a collective – all living things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My guess would be that your dogs and cats have aided and abetted that feel of being in a huge living collective Moisy. I’m even concerned for the welfare wasps and slugs as I get older – and wiser?

LikeLike

What a story! Thanks for putting it out to be shared, Kev.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was delivered in true journalistic detail and clarity, Kevin. I adore Faulks’ idea of doctors relating in a human way to mental patients and even sharing their own truths, but if out of the box thinking like that existed, the world would definitely not be the one we’re living in, I don’t think.

Your social story eerily mimics my own and probably so many others! I used to just think I was shy, and I was, but it was there for a reason. Your description of crowds and get-togethers and the exhaustion of constant engagement–I know it well, Kev! When I got older and could manage the art of small talk pretty well, if it lasted fir an extended amount of time, I started feeling punch drunk and seriously needed to lie down and close my eyes. I remember going outside and down the driveway at a party once and feeling very relieved and relaxed to just have a one-on-one conversation with security. No idea why security was there. This was a looooong time ago.

But we made our way and found a rhythm, didn’t we? And did better than just survived. Your family is beautiful, by the way. I love all of the pics. 🙂 🙂 🙂

Stacey

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for taking the time to read it Stace. There is still a part of me that would like to be able to effortlessly adapt to any social situation, but it isn’t to be. Alcohol was my scaffolding in so many past interminglings, but booze in any quantity doesn’t really agree with me any more. A friend made the pertinent comment, in empathy, that I simply lack a ‘bulletproof social persona’. I like that description.

Writers are inclined toward introversion, I guess. What’s your level of crowd interface these days?

The coming of spring – and the lengthening of the days – is a big boost for me every March. Eight months looming ahead of consistently outdoor life. Of course if I was rich enough we could spend every winter in Antigua, Sri Lanka, Cape Verde or somewhere equally warm. I do love the sunshine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I love the days when the sun sets at 8 pm. They’re coming up fast here in LA! Setting the clocks forward and all that (even though they should have gotten rid of that idiotic daylight savings long ago). But of course it’s not as cold as where you are. Hubby used to look forward to spring, though, as a kid, because he couldn’t stand winter (having grown up in Brooklyn). I wish you were rich enough to move to Cape Verde, too, ’cause then I could come visit, lol

My level of crowd interface these days is nil, Kevin! Just ’cause I’m working all the time. The most we’ll do is manage a movie up the street now and then, and of course the theater will only have about 10 to 20 people in it, usually less, because it’s just unaffordable now. I don’t even know the last time I was in a crowd or with a bunch of folks where I had to shoot the shit. It’s been so long! One thing, though. I was in an interview six months after I got laid off and realized I was SO out of practice for interviews it was almost criminal. One of the things I was asked was what I would contribute to the company on my first day of work, and my mind went blank, I was suffused with rage, and I never did come up with an answer!!! lol I was thinking, “My first day of work?! Are you shitting me? What the [bleep] am I SUPPOSED to contribute? Isn’t my being there enough? What, I have to lick your boots now with endless simpering thanks for making me into a slave, staying here for 9 1/2 hours (you had to make up for lunch by staying an extra hour) and never seeing the sun or the sky again??!!”

I realized later I could have said something like, “Enthusiasm,” or “Well, I WON’T bring a knife to kill all of you, so restraint would be a positive, wouldn’t it?” But not then, not in the midst steam pouring from my ears. I couldn’t not think of one thing to say.

So…out of practice in crowds AND out of practice at interviews, too! lol 🙂 🙂 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen a few movies recently – two with Maureen, where there were 8-10 others in the cinema, and one alone, where I had 4 ‘companions’. It’s a dying culture here. Of course my inner introvert loves the fact that you can focus on the film, rather than get irritated with nearby others looking at their phones, chomping on food, guzzling drink, rustling their confectionery papers and chatting.

Those replies you kept a lid on might have worked though. Nobody really wants to hire desperate people – or do they?

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, no one DOES want desperation, Kevin. I guess the ultimate problem was that it was a job I didn’t like the description of and didn’t want to do but felt I had to at least interview for it because we can’t can’t always get what we want, but if we try sometimes, we get what we need. And, yes, I AM quoting The Stones!! lol

As for movies, same here. It’s not just dying–I think it’s dead. Not just theaters, but evidently studios and filmmakers and everyone else is moving/has moved out of LA and Hollywood is now like an old, withered hooker with a bunch of makeup piled on and a short skirt, but it’s not fooling anybody! lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

I sing that Stones song to Maureen sometimes Stacey. 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course! 🙂 🙂 🙂

LikeLike