The year after the hair grafts was a struggle, trying to come to terms with what felt like an act of self-mutilation. I worked to build up some funds, while staying away from friends until my appearance had some kind of congruity.

But despair floored me regularly, back at the parental home. The paths back to the juice and energy of 1976-78 had disappeared. I kept smiling, kidding myself and others that all would be well. Inside, utter anxiety not only at my own post-transplant plight but at what you had to do to get on in the world. My contemporaries were signing up for careers, treading hierarchical corporate paths in some cases. From my gloomy, jaundiced view, they were throwing away the key to the glorious joy ride of being young.

Nonetheless, within a relatively short period, a new source of energy infusion showed up. It would eventually drive me out of bed while others slept, and sear untold neural pathways through my cerebrum for over three decades. It had probably always been close, lurking in the genes, waiting for the trigger.

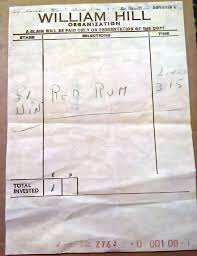

In early June 1979, just after my finals, I was preparing to return to Essex. Worrying incessantly about my bloody hair, I noted that it was Derby Day at Epsom racetrack. The fiver left in my bank account was then tradeable for at least 10 pints, and a far greater sum than I had ever thought to wager. But I thought: ‘Why not?’

Strolled in the late spring sunshine to a local bookmaker, and placed the blue note on Troy. It was recommended by a tipster in the copy of the Sun pinned to the bookie’s wall. No other reason. Went back home and listened to the race on the radio. With a substantial amount of fear. So I almost jumped through the roof as the commentator announced that Troy was eating up the ground on the outside of the pack. It won by a streak, marking my first ever “high” from a winning bet. Waves of pure joy flooded through me as tension dissolved into relief. I could now pay my last month’s rent with the £30 profit. That was the breakthrough bet, hook wager number one.

A month on, working at Maylands Golf Club in Harold Park, Romford, I started to become fully aware of Britain’s deep-seated gambling culture for the first time. Eric, my dad, had somehow made the startling transition from scrap metal merchant to club secretary. For every big golf tournament, he would chalk up an odds blackboard so that the players could bet on themselves or others.

In the golf club bar where I worked some afternoons and evenings there was a constant dwelling on horse racing among a group of businessmen who were privy to inside information from various stables. Astonishingly, many of the tips seemed to win, especially in the biggest races. Punts by these guys on Known Fact in the 1980 2,000 Guineas, and Popsi’s Joy, ridden by Lester Piggott in the 1980 Cesarewitch, spring to mind. Both of these selections were tipped to the bar proprietor, Jack Townsend. Quite reasonably, my brain asked how anyone could possibly predict the outcome of contests where temperamental four-legged beasts were steered by dwarves.

They surely could not, but I had already commenced betting in 5 and 10 pence doubles and trebles. Nothing the size of the Troy bet, but with the occasional 50 pence or £1 win single if feeling highly inspired. The kindlings of a new world were lit beneath me.

A betting shop a few hundred yards away became the subject of a visit every lunchtime. My ears pricked up hard if anyone voiced an opinion about this game, including Reg Brown, an old-timer who slept in the stables at the club and caddied for beer money. Brother Neil was happily helpful, unloading his decent knowledge whenever I asked.

The tips didn’t always win. Tony Palmer accompanied me in June 1980 to Epsom to back Noble Shamus in the Derby. The horse started at huge odds, 200/1 or something equally silly. For all I know, Noble Shamus is still running.

A few weeks later, I took a series of trains across from Essex to Ascot, on a Saturday morning whim borne of multi-level alienation from the world. I could think of nothing better to do.

At the racetrack, I gained access to Tattersalls, the enclosure for the plebs, away from the top hats. Piggott was booked for Popsi’s Joy in the opening 2 mile handicap. Robin Goodfellow of the Daily Mail had made this one his nap (best bet of the day). 7/1 appeared to be a nice price. I wagered £3 to win. Popsi’s did the job, not for the last time that season, with Lester’s arse characteristically jutting towards the sky as they passed the post.

Via Delta was the Sporting Life nap in the next race, a 5 furlong ‘sprint’. It went off as the 3/1 favourite, carrying £5 of my dosh. And won by a length. Astonishing.

So I risked £10 of my £36 profit on Fingals Cave, who trotted up at 2/1 in a middle distance race. My next wager bit the dust, so I quit the joint, about £50 ahead, and went on a solo drinking tour of the West End.

Hook number two. £50 was good money in those days.

My experience of drugs was limited. But the sensations from backing winners were comparable to some of the best outcomes I had known from beer. That newborn feeling as the first pint or two kicks in. To be clear, I realised that such a profitable day bore no relation to any discriminative skill on my part. I got lucky, and knew it, but had experienced a genuine high, and a bulging wallet. As I paced from London bar to bar, it dawned on me that a learning curve might be available. So that my betting could be steered by my brain in a way that would yield both steady profits and mental ecstasy on a regular basis. Was this near-perfect mix of the visceral and the cerebral not something worthy of pursuit? Or was DNA just doing its irrepressible thing?

It was a slowly opening world. With such mighty food for thought.

At some stage, I had acquired a view – much to my mother’s horror – that most work was for mugs. The massive influence here was American author Henry Miller, whose books I had begun to read in mid-1979 as if they had been written for me personally. Drop out my boy, cajoled Hen. Read, drink, fuck, write, wassail, sleep, travel. But don’t become part of the system, don’t sell your soul. Work to live, if indeed you must work at all.

Similar veins of discourse had issued from many of the writers in the New Musical Express. These reinforced my critical knowledge acquired from years living on a grant. You could live like a king on next to nothing. And in my opinion have a better time than any accountant, doctor or lawyer. Only a handful of my pals thought identically, Steve Lowndes being the most prominent of these. Between us we hatched a myriad of plots and plans to subvert the received order.

My basic tactic then and in the years ahead would be to hold down a manual job for as long as I could stick the boredom, and then rest and plot again. I have never been lazy, and the reality was that most of my occupations have clocked up far more than 40 hours a week. I drifted into simple occupations where the automatic nature of the activity usually allowed me the undisturbed space to dream. From 22 until the age of 35, when my years as a journalist began, I worked as barman, greenkeeper, the Thermos nightshift, caring for vulnerable adults, a short teacher training spell in Canterbury, then ice cream salesman, window cleaner and milkman.

A dream came to me in the summer of 1980. Just before disappearing to Greece for three weeks with my friend Mike Beaver, I dreamed of a horse that won a race. Its name was My Mind Told Me.

Back in Harold Park after a delicious holiday, the rattle of the hooves down the racetrack was increasing shaping as my rapture runway. Dad would occasionally buy me the Sporting Life, which I would consistently bin due to the excessive level of incomprehensible detail. Given that I saw next to no future for myself in terms of a career, it was a puzzle that would clearly require much harder work.

In the meantime, I read the views and followed the selections of the tipsters in The Mail and Telegraph, which my parents subscribed to. As the racing card steadily came to form the most important part of each day, it dawned that I needed to make the jump away from the opinions of others into a logical selection method. Maybe one plagiarised from a winning punter. Or perhaps as a result of a joyous new quest to figure out which parameters counted crucially in horse racing.

As a working hypothesis, it was no bad starting point to recall that at school you could predict with some certainty which peers would win or place in a 100 yard sprint. Same result, time and time again.

The key difference with horses was that in most races (called ‘handicaps’) they carried differing weights, to level their chance of winning. Nonetheless those running well in recent races would win more often than those who were out of form, weights notwithstanding.

To drill down into these ideas, I began to read a weekly publication by the name of “The Sporting Chronicle Handicap Book”. It served as my personal toe in the door for the comprehension of racing form. A new language to master, pivoting around numbers.

The key, I continually told myself, was the will to learn, which would be required incessantly to drive past the countless setbacks that would inevitably lay ahead.

Around the time of the Ascot visit, I would often stay with John Madden and Tony Palmer in Hammersmith, London, at the weekends, and would never fail to be amazed at the wealth oozing out of the capital. While it looked attractive, the necessary grind of 9 to 5 in a suit and tie seemed like a terrible and unoriginal way to go about inhabiting a human body.

40 or so years later, I give the young Kevin a huge thumbs-up and a big wet kiss for following his heart, and doing his own thing, however naïve it may have been.